Buky Schwartz: Re-constructions

The following post describes my MA thesis project report:

Re-constructions: Preserving the Video Installations of Buky Schwartz

The report includes installation specifications for two video installations:

Spring 1981 (1981) and Three Angles of Coordination for Monitoring the Labyrinthian Space (1986)

I recently completed my MA degree thesis project on the conceptual artist Buky Schwartz. Schwartz is perhaps best known for the video installations and single-channel video art that he created during the 1970s and 1980s. His estate's collection of photographs, video tapes, and other forms of documentation embody the artist's legacy as well as the key to preserving his artwork. You can watch my presentation on the project above, or read the full report.

- My thesis report contains a research narrative that describes the artist's oeuvre and is meant to contextualize the collection through the lens of contemporary museum practices regarding video installations and conceptual art.

- The thesis also includes a collection assessment detailing the contents and condition of the estate of Buky Schwartz's collection.

- To demonstrate the feasibility of realizing one of Schwartz's video installations through the documentation in the estate's collection, I created display specifications for two of Schwartz's works: Spring 1981 (1981) and Three Angles of Coordination for Monitoring the Labyrinthian Space (1986).

- Because the analog video in the collection should be considered at risk, I have also prepared a Request For Proposals (RFP) for the digitization of the analog video in the collection.

I've put a few excerpts from the thesis below, but I would invite anyone who is interested to read the full report, or review the display specifications for Spring 1981 and Three Angles of Coordination for Monitoring the Labyrinthian Space.

A closed-circuit camera system or CCTV, often used in surveillance technology, sends the “feed,” or video signal, from a camera directly to a monitor. We now often see these in supermarkets and gas stations. Because we are accustomed to the constant presence of video in our daily lives, the aesthetic implications of our interaction with this technology--the psychological feedback loop created as “I” look at a camera’s view of “me” in this “space,” rendered flat into a plane on the monitor- -often goes unscrutinized or unquestioned. That is “me,” “here. ” The artist Buky Schwartz interrogates these assumptions of video technology’s seemingly objective reproduction of space through his video installations.

The Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) acquired Buky Schwartz’s first video installation Painted Projection (1977), in 2014. The work consists of a strategically placed camera, monitor, and paint on the gallery floors and walls. The effect of the work is a seemingly abstract or incoherent pattern on the walls and floors of the gallery in physical space, and the confrontation of the same space represented on the monitor, but with the pattern presented as a coherent representation of a geometric form, a cube. The museum’s approach to the work is rooted in research based on documentation of the 1977 exhibition Painted Projections at Julie M. gallery (which was the first and only public exhibition of the piece), dialogue with the estate, and documentation of Schwartz’s studio study, that was created immediately after the exhibition.

These installations that Schwartz created in 1977, the two works featured in the Painted Projections exhibition, and the cube study, all function as expressions of the same concept, an idea Schwartz was working out over the course of a year. The SAAM acquisition reflects this thinking, incorporating the multiple iterations of the work into the acquisition, rather than arbitrarily relying on one instantiation. And, at least based on the 2015 exhibition, preferencing the latter form of the work. This form of the work was never truly “fixed” in an exhibition, or in formal documentation such as installation instructions crafted by the artist, leaving this process of determining the identity of the work to the SAAM. Through dialog with the estate and further research, the “script” for realizing the work (the installation instructions), developed, and continues to develop as the work is “formalized” in the collection. (1) (2) (3)

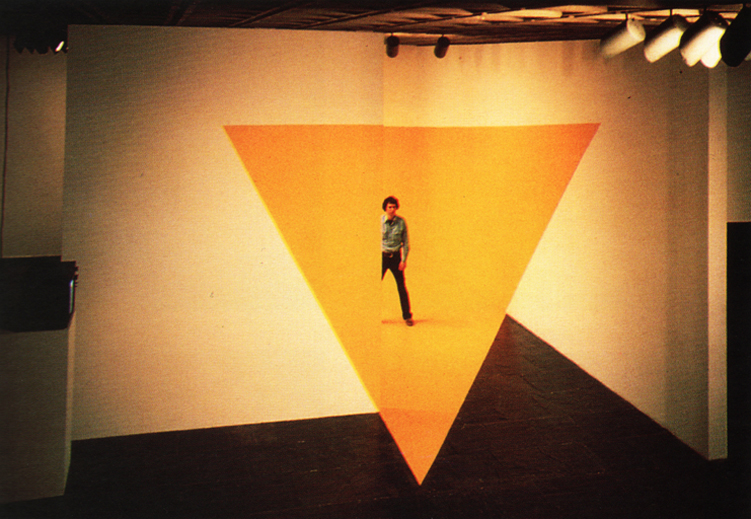

Yellow Triangle (1979) was acquired by the Whitney in 1992, under the guidance of John Hanhardt. Similarly to the SAAM’s acquisition of Painted Projection, the Whitney received a set of instructions for realizing the work and photo documentation of the piece’s initial installation. The difference being, these instructions were drafted under the supervision of the artist. The instructions, therefore, are far more specific and refined... [One] significant difference in the acquisition is the inclusion of a recording from the camera’s perspective during the installation, presumably created by simply including a VTR (Video Tape Recorder) in the closed-circuit signal path. This recording is used to demonstrate the size and location of the desired triangle that ought to be realized on the monitors in the gallery, as well as having incredible value as documentation of museum attendees’ interaction with the installation.

In the Yellow Triangle installation instructions, Schwartz asks that the recording be used as a guide, and that the technician installing the work trace the triangle directly on the monitor using a felt pen. Then, this traced pattern is superimposed on to the space, by sending the signal from a camera, positioned in the gallery according to Schwartz’s specifications, directly to the monitor (the closed-circuit that will be used in the installation). From this point, one technician should “sit directly in front of the screen” and guide a second technician “in marking the walls and floor at key points in the room as identified along the triangle on the screen.” (4) In this way, the pattern is taped out in physical space, and then painted in. Schwartz adopted this process early in his career and continued to practice this methodology thereafter. This technique has been described by several of the artist’s former assistants and in a published account as well. (5)

Spring 1981, is the first in a series of three installations, including Fall 1981 (1981) and Summer 1981 (1981). These works all have a similar structure. A group of tree stumps (15-25) of varying height are arranged in the gallery, with an easily recognizable geometric pattern (or patterns) painted on them. However, as is the case with many of Schwartz’s video installations, the pattern is only recognizable from the privileged perspective of the video camera, delivered to monitors in the gallery via a closed-circuit system.

Schwartz kept a series of 3.5” x 5” prints of the first installation of Spring 1981, which show the artist and various assistants arranging the tree stumps, setting up the closed-circuit camera and painting out the two geometric patterns, a square and a triangle, onto the stumps. Stored with these prints is an installation manual, with the title Timber written at the top, which closely resemble the three works in the “Seasons 1981” series. There is no documentation or publication that mentions Timber, therefore it appears this was a working title, a concept that eventually was realized as Spring 1981. These documents demonstrate how the physical components that are necessary to the work are arranged. There are also several published accounts and descriptions of this work, which provide the dimensions of the initial incarnation of the installations, quotes from Schwartz about the work, and also detail the series’ exhibition history.

The goal of the display specifications is to codify the identity of the artwork, much as the museums that have collected Painted Projection and Yellow Triangle have done. While establishing thorough guidelines and instructions for installing the piece, the variability of several elements is emphasized, with the intent of making it clear that each iteration of the piece will be unique.

Three Angles of Coordination for Monitoring the Labyrinthian Space (1986) has had several iterations, making the work attractive for this project, as it has had the opportunity to develop. The first iteration of the piece, exhibited as Untitled 1986 (1986) or referred to under its working title Maze, is modest in scale in comparison to the subsequent versions. However, the basic functionality and intent of the work remains. Three Angles of Coordination is made up of thin walls that rise above eye level, arranged in a maze composed of three-wall modules, each 120° apart. In order to navigate the maze, the viewer must rely on monitors placed above the maze walls, displaying a bird’s eye view of the structure, fed live to the monitors from a camera hung from the ceiling. While this initial version used monitors hung from the walls around the edges of the gallery, all of the later iterations of the installation mounted the monitors on to the junctions of the three-wall modules, dispersing them across the maze.

The estate holds a large amount of documentation of Three Angles of Coordination, including prints of the realized work (especially in its second iteration at the Mattress Factory in Pittsburgh), a floor plan of the maze, sketches of the monitor mounts, and 3D models of the work. Shlomit Lehavi, a lifelong friend to Schwartz, and at one time the artist’s assistant, was interviewed about the artist’s process in January of 2016. Schwartz would first sketch ideas out on paper, then work out the mechanics of a particular installation by building scale models. The 3D models in the collection, then, have significant value, as they can be used as a basis to “scale up” an installation. There are several models of Three Angles of Coordination, in varying condition. However, each provides insights into the scale and layout of the installation. Each of the models is consistent to the proportions of the others, as well. The display specifications for Three Angles of Coordination are based on measurements of the models, documentation of the installation, published information describing the work (such as dimensions, the artist’s statement, interviews that discuss the installation, etc.), and the artist’s sketches and floor plans. Just as was the case with the “Seasons 1981” series, the specifications are designed to allow for variability, as the work never had the exact same dimensions or layout.

If you would like to learn more about Buky Schwartz and see more of his work, please check out the estate of Buky Schwartz's website.

Eddy Colloton

August 2016

Citations

(1) Pip Laurenson, 'Authenticity, Change and Loss in the Conservation of Time-Based Media Installations', Tate Papers, no.6, Autumn 2006. Accessed May 2, 2016. http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/06/authenticity-change-and-loss- conservation-of-time-based-media-installations.

(2) Phillips, Joanna (2012). “Shifting Equipment Significance in Time-based Media Art” in The Electronic Media Review, Electronic Media Group, Vol. 1, p. 139-154.

(3) Mansfield, Michael. "Interview with Michael Mansfield." Telephone interview by author. December 09, 2016.

(4) Schwartz, Buky. "Instructions for the Installation of Yellow Triangle." Buky Schwartz Artist File. The Whitney Museum, April 2, 1992.

(5) Pincus-Witten, Robert. "Buky Schwartz: Video as Sculpture." In Buky Schwartz, Videoconstructions, edited by William D. Judson, 19-22. Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Museum of Art, 1992.